Organizing Your Data and Keeping Them Safe

In this lesson you will learn

- Why solid, systematic organization (e.g., clear and consistent naming of folders and files) is important

- Some strategies for working with “unorganized” data

- The difference between keeping data “safe” and keeping them “secure”

- Key strategies for keeping data safe and secure

Initial questions

- Is there a “right” strategy for organizing and naming folders and files?

- Are you using any tools that help you organize your data? Which ones work well, and which ones work less well – and why?

- You spend a lot of time collecting your data; how much time have you spent thinking about keeping them safe and secure?

Naming and Organizing Folders and Files

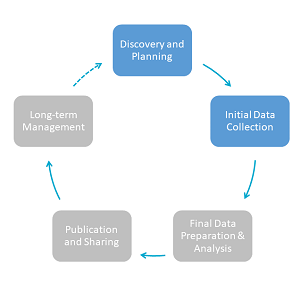

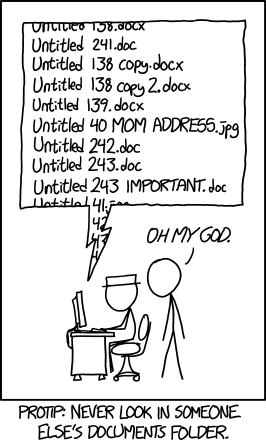

Keeping your data organized is one of the key principles of data management. The advice we offer here may be some of the simplest we offer in this course. It’s also the type that’s most commonly ignored, with negative consequences for research. Two key initial steps of data organization are creating a consistent folder structure and standardized filenames.

Source: https://xkcd.com/1459/

Folder Structure

Your folder structure should reflect how you think about your project. Create the folder structure at the outset of your research and write a short memo to yourself describing its logic. For instance, you might organize your folders geographically (site 1, site 2, site 3), by the types of materials (interviews, web sources, scans), chronologically by events that you’re studying, or by research trips. Regardless of the structure you choose, a coherent, logical folder structure helps you to organize your files consistently and thus to easily locate all of your files in the present and the future. As research rarely goes exactly as planned, you will likely need to make adjustments to the structure of your folders as you go along. These should be purposeful, and reflected in your organization memo. Think about how a particular organizational change might affect, and should be reflected in, other aspects of the organization of your folders.

File Names

Similar to folders, there is no single right way to name your files. No matter what convention you adopt, as with your folder structure, we suggest that you develop it at the start of your research project, make a note of it in the same memo in which you outline your folder structure, and apply it to your files consistently. Beyond this, we can offer some general advice:

- Avoid special characters such as :/&@ as well as spaces, as they can cause problems on some file systems

- Avoid overly long filenames, which will cause problems on Windows (25-35 characters + file extension is a good rule of thumb, though don’t worry if you have a few more)

- We recommend including the date on which the file was created – as YYYY-MM-DD or YYYYMMDD (known as ISO format) – in the same location in every file name (e.g., at the beginning or at the end).

- Include organizational and easily identifiable elements such as short titles or locations in filenames

Here are two examples:

Argentina\_InterviewMeyer\_20180715.docx

BNA\_Embassy\_Poland\_19531118.pdf

You will often need to create more than one version of a file. If you follow a consistent file naming convention, including the date on which the file was created, you will always be able to immediately tell which version of the file is the most current. This is a better practice than including “FINAL” or “CURRENT” in the file name. As the back-ups of your files will mirror this file-naming convention, the same principle will hold should you need to resort to them.

Exercise

Folder and Filename Assessment

- Open the master folder for one of your current research projects and candidly assess how clearly and consistently you are naming your folders and files. Consider, for instance, the following:

- How many levels of folders do you have – levels within levels within levels? Are there enough levels, too many, or too few?

- Can you tell, without opening a folder, what is in it?

- Is there some logic behind the organization of your folders, or does it seem you just created a new one whenever you needed one?

- How consistent are the names of your files?

- If you have multiple versions of particular files, can you tell which is the most current?

- Create a new document (clearly named!) that will be a draft of the memo to yourself about the organization and naming of your folders and files. Create the first few bullets under “folder organization and naming” and under “file organization and naming” that could serve as instructions to yourself for (re)organizing and (re)naming your folders and files.

Organizational Tools

Instead of relying on your computer’s operating system to organize files and notes, you can use tools designed for this purpose. There are various types: reference managers such as Zotero or Endnote; qualitative data analysis tools like NVivo, atlas.ti, or Dedoose; and document management tools such as DevonThink Pro. All of these tools include search and organizational functions beyond your operating system’s capacity. However, this functionality comes at a cost – sometimes financially, often in the form of time you have to invest in learning new technology.

Whether any of these tools is right for you depends on the nature of your data/files, your budget, and your personal preferences.

- Do you have the funds to pay for software (and future subscription costs or version updates)?

- Does the additional functionality these tools offer provide tangible benefits and time saving to you that make it worthwhile to add another software product to your “toolchain”?

As you choose a tool, be particularly mindful of “lock-in”, i.e., your ability to get information back out of the tool should its producer cease operation or should you want to switch to a different tool.

- Does the software export into open, widely read formats?

- Are there freely accessible ways for other software to read the data (often referred to as “Application Program Interfaces” – APIs)?

- Can you read the data without exporting it (i.e., without access to the software) – that is, is it stored in open formats?

Finally, tools facilitate organizing your data, but you still need to devise that organization and apply its logic consistently. When using any tool, follow the same general planning guidelines and organizational principles outlined above. We have included some further resources on choosing tools and on using some of our favorite tools at the end of this lesson.

Working with Disorganized Data

Not everyone keeps their data well-organized. If you are confronting disorganized data (whether you, or someone else, generated them) we suggest the following approach to organizing the data: spend just enough time so that you can effectively use the data, but not more time than what good organization will save you.

If the disorganized data are your own, and you fear (or know) that they are scattered in many different places on your computer, your first step may simply be to track them all down. Your computer’s operating system’s ability to search for files is far more powerful than you may realize. Operating systems can search filenames, as well as the full text of most common file formats (as well as text in the file properties). Thus you can, e.g., search your entire hard disk for PDFs created in 2018 that contain the term Korea or Korean and then show them in a (virtual) folder, helping you to impose some order on chaotic file collections.

The major operating systems have different, but quite similar search options.

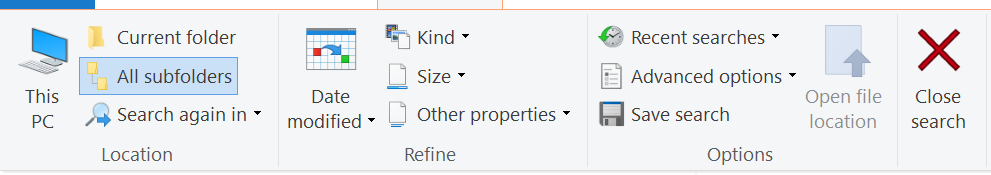

In Windows, the most useful search tool is the * as a wildcard for multiple characters. For example, *.pdf will find all files with the pdf file extension. Once you start searching in Windows, you can also open the search tools:

You can specify file sizes, the date a file was modified, or the kind of document (e.g. “image” will find any image format).

The “Save search” option is particularly useful. This allows you to save a search that you performed (and the results); when you re-open the search, you see a folder filled with files placed there automatically by the search functionality. Even better, the folder updates automatically as you create new files that match the search criteria (or delete files).

Macs offer powerful file search via the “Spotlight” tool. By using shortcuts such as kind:PDF and dates like created:MM/DD/YYYY (preceded by < or > for any date before and after respectively), you can generate similar searches as for Windows. Spotlight even understands “natural language” requests (powered by the same technology as Siri) such as “Show me all images created since May 30th this year”.

Mac’s facility for saving searches is called “Smart Search”. You can create smart folders in the “File” menu of Finder and then add additional search conditions (or change existing ones) at the top of the folder.

Once you have gathered a particular set of relevant files, you can impose additional order using a file rename tool. With the free-to-use Bulk Rename Utility, you can prepend or append text to a set of filenames, can replace words or characters, and carry out many other functions. You can use this to add a consistent structure to file names or to normalize how you’ve named files.

Keeping Your Data Safe and Secure

Two other key aspects of data management are keeping your data safe (preventing loss), and keeping them secure (preventing unauthorized access). It’s important for you to know how to accomplish both without placing undue burden on yourself when you’re conducting your research.

Backing Up

There are few research experiences that are quite as crushing as losing data. Consequently, “back up often!” is a standard exhortation – you have likely said this to yourself and to other researchers many times. Thankfully, technological advances have made it easy and cheap to protect against multiple types of data loss.

Data loss can take many forms:

- Hardware failure: your hard disk crashes, preventing you from accessing your files

- Software failure: due to a software bug, a previously functioning file is overwritten with a corrupted, non-working version

- Loss of equipment: your computer is stolen or destroyed

- Malicious attack: your computer is infected by ransomware that locks access to your files

- Human error: you accidentally make changes to a file and save, overwriting the previous version.

Your backup strategy should protect against all of these. We suggest three rules of thumb.

Have at least three copies of all important files. Multiple copies help to protect against data loss and also allow you to establish the “correct” version of a file if two copies are contradictory.

Store your files in at least two different physical locations. Storing files in multiple locations protects you in case of loss of equipment in one location due to theft or natural disaster.

Make backups regularly, automatically, and incrementally. Automated backups take the responsibility for (and worry about) backing up off your shoulders and make it easy to have daily, even hourly backups of your files. Incremental backups only back up files that changed since the last time you backed up; this allows you to revert to previous versions of files or restore deleted files.

Following these suggestions does not require a complex set up. For instance, the following would do the trick:

- Create automated and incremental backups to an external hard disk using Mac’s Time Machine or Window’s File History.

- Automatically sync your data with a cloud service such as Dropbox or Box.com.

Finally, don’t neglect to test your backups, i.e., make sure that you can actually get back the files should you need them. (If you’re inclined to skip this step, watch this video on how Toy Story 2 was almost lost in part due to a failed backup.) Again, testing your backups need not be complicated: Once a month, select a handful of files in different folders and make sure you can open them in your backups. Choose different files every time.

Security

Basic security measures are a must to prevent your accounts from being hijacked (and potentially data deleted) and/or malicious software from being installed. Preventing unauthorized access to your data is particularly important if your data are sensitive and confidential. We provide a basic outline of best practices below. If you’re handling sensitive data, you should consult with experts at your institution and review the additional guidance we list under resources at the end of this lesson.

Passwords and Authentication

Here are the main ways attackers gain unauthorized access to user accounts:

- Mass Theft: Re-using email/password combinations stolen from insufficiently secured databases

- Brute Force: Guessing common passwords, passwords that include dictionary words, or short passwords

- Phishing: Fooling you into entering your username and password on a page the attacker has created to look like a legitimate page, often prompted by an email (this is, e.g., how the 2016 hack of the Clinton Presidential Campaign took place)

- Software vulnerabilities: By exploiting known vulnerabilities in your operating system or browser to install malicious code and/or view your activities

How can you protect yourself against all of these threats?

Use complex passwords: The longer and less-intuitive the better; numbers, symbols, and a mix of lower and uppercase letters add complexity.

Do not re-use your passwords across different user accounts: Mass theft of databases makes re-used passwords a critical vulnerability.

Be wary of links to login pages. When in doubt, do not follow the link and log in via a service’s homepage instead.

Always keep your software (especially browser) and operating system up to date and make sure automatic updates are turned on.

Technical tools can help you protect yourself and significantly lower the burden of security. Most importantly, password managers help you to automatically create unique, secure passwords and keep track of them, effectively automating 1. and 2. above. Two-factor authentication (2FA), offered by an increasing number of providers, offers additional protection for both hacked passwords and phishing. 2FA requires another authentication step in addition to passwords. This can be a temporary code, as supplied via text message or a cell phone app, or a dedicated USB key. (Experts advise that text messages are far less secure than the two other modes of 2FA, and USB keys provide the strongest protection as they cannot be spoofed.)

Secure Communication

If you need to communicate securely while conducting research, for example, with members of your research team or human participants, messaging apps on your cell phone are often the safest choice as they strongly encrypt all communication. For highly sensitive topics, apps with a focus on privacy and security like Signal are ideal. However, the vastly more popular WhatsApp provides similar encryption and is likely already used by your interlocutors.

When you have to rely on e-mail for communication, the Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) standard provides state of the art protection via encryption, but is not currently widely adopted.

Secure Devices

Ensuring that the devices you are using during research remain secure (inaccessible to others) is critical. Most attacks capitalize on known vulnerabilities in operating systems and browsers, so keeping your software up to date (and relying on automated updates) is critical. For most users, software updates coupled with a reasonable sense of caution (don’t open sketchy links; don’t install software from any source you don’t trust 100%) will provide reasonable security.

If your research is highly sensitive, especially if you suspect it may attract the attention of technically sophisticated attackers (such as governments), we recommend additional care. Mainly due to Apple’s commitment to providing operating system (iOS) updates to all its phones, iOS products provide vastly superior security to most Android devices. (If you do use Android, ensure your phone is using a recent version of the operating system.)

Encryption

Especially if you are travelling with a laptop, you should ensure that your hard disk is encrypted. This is a standard feature of operating systems, referred to as “File Vault” on Mac and “Bit Locker” on Windows. Without disk encryption, anyone who gets access to your computer can read all your files, even if they do not know your account password.

For particularly sensitive data, consider using a dedicated encryption tool such as Veracrypt for additional security.

Exercise

Data Safety and Security Self-assessment

- Take QDR’s Data Safety & Security Self-assessment here and see if and where your current practices need improvement. If there are things you want to change, make at least one such change immediately.

Further Resources

- The CAQDAS Networking Project at the University of Surrey has a terrific guide to choosing the appropriate CAQDAS tool.

- Harvard University Libraries suggest using the Zotero reference manager to stay organized in the archive.

- The open source software Tropy was designed specifically for managing images taken during archival research. A review in Perspectives on History describes its functionality and vision.