Sharing Data – Considerations, Benefits, and Challenges

In this lesson you will learn

- Some of the key questions you’ll need to ask yourself as you consider sharing your research data

- Some benefits and some challenges of sharing research data

- How different organizations in the academic ecosystem influence when, where, and how research data are shared

Initial questions

- Have you ever shared any of your data?

- If you have shared your data, why did you do so? If you haven’t shared your data, do you have specific hesitations about doing so?

- Have you ever used data shared by other researchers? If so, was it easy or difficult to access the data? How easy was it to use the data?

What Does “Sharing Data” Mean?

Carefully managing your data (discussed in Modules 1 and 2 of this course) makes them more valuable for your own research, and this is the main reason why data management is so important. However, effectively managing your research data also makes it easier for you to share them with other scholars, and makes it more likely those other scholars will be able to interpret and understand your data.

As you probably know, sharing qualitative research data is a relatively new – and not uncontroversial – idea in the United States. While sharing such data is more standard in some European countries, and in the U.K. in particular, among U.S. social scientists there has been a very weak tradition of sharing qualitative data. As we discuss in greater detail below, since the early 2010s, various social science disciplines in the US – and political science in particular – have been engaging in vigorous debate about the promise of, and problems with, sharing qualitative research data. Further, various stakeholders in the research lifecycle (funders and journals, for instance) have begun to call for the sharing of more data. Simultaneously, new technologies to facilitate data sharing are being developed.

If you join the vanguard of scholars who are sharing their qualitative data, there will be lots of decisions that you’ll need to make when doing so. We mention them here, and offer information that will help you to answer them in the subsequent lessons in this module.

- How much of your data will you share? Sharing data is not an all-or-nothing procedure. Different aspects of your data – particularly if they were generated through human participant research or are under copyright – may be under different types and degrees of constraint.

- How and where will you share your data? There are several options, and major advantages to sharing your data in an institutionalized venue.

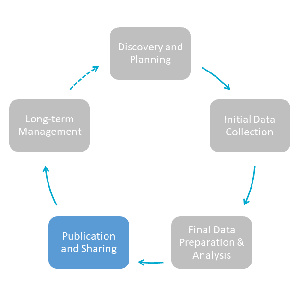

- When will you share your data? Will you share them while the research project with which they are associated is ongoing, or only afterwards? Might you share the data when you submit an article for review, or just before publication? Organizations that funded your research or journals where you wish to publish it may have rules that you’ll need to follow.

- With whom will you share your data? With anyone who wishes to access them? Or is there a justifiable reason to limit access to your data in some way?

These are all choices that you should begin thinking about even before you start to collect data. While there are rarely “right” or “wrong” answers, well-considered decisions will allow you to contribute the most to your research community, and to the production of knowledge.

No matter how you answer these questions, sharing your data only makes sense if the data will be meaningful to other scholars. Sharing data requires preparing the data and creating documentation such that the data can be interpreted and used by others. Since you will have effectively managed your data – such that the “future you” will be able to understand them – you are already many steps ahead in this process. Nonetheless, you may have to take a few extra steps to make your data legible to others. For instance, you might prepare slightly more detailed documentation, obtain some additional permissions, or perhaps de-identify the data (if they were derived from interactions with human participants; we discuss this process in the next lesson).

Reasons to Share Data

A fundamental question not included in the list of questions above is why. Why would you share your research data? There are lots of reasons why sharing your data is a good idea.

First, let’s consider your point of view, as the researcher who generated the data. Sharing your data:

- Helps you comply with external mandates:

- Scholarly associations may have recommendations or guidelines about data sharing. In the US, this is the case for many social science associations including the American Sociological Association (ASA), the American Political Science Association (APSA), and the American Psychological Association (APA).

- The organization(s) that funded your work may require that you share the fruits of your research with the broader scholarly community; indeed, you may have to describe your plans for sharing your data in a Data Management Plan that you submit with your funding application.

- Journals may require that you make the work you publish with them transparent by sharing the data that undergird it.

- For instance, more than 25 political science journal editors have signed “JETS” – the Journal Editors Transparency Statement – supporting the development of transparency requirements.

- Provides for long-term safe storage for your data (if you deposit them in a repository).

- Helps you demonstrate the rigor and power of your analysis.

- Increases the visibility of your work and potentially your citation rates, enhancing your reputation.

- Enables you to make new connections to and perhaps collaborate with other scholars.

If you carried out interviews or surveys or otherwise generated data through interacting with people, another set of reasons for sharing your data relate to those individuals. Your “human participants” can also benefit from the broader sharing of the information they provide to you. Sharing human participants data (with the permission of those respondents):

- Allows a broader population to learn from and capitalize on the important effort that interview respondents invested in answering your questions.

- Can help to minimize negative effects that data collection may have on the subject population.

- For instance, if the topic of a particular set of interviews is very sensitive or traumatic, it can be difficult for interview respondents to answer questions. If you share your data, that community doesn’t need to repeatedly relive their difficult experience as they are questioned about it by different researchers.

- Allows your respondents’ voices to be amplified. Some populations are hard to reach and others have not had a voice for other reasons. Sharing the information that they shared with you allows their views and perspectives to be heard.

- Allows a scholar who plans to interview members of the same population that you did to learn about his respondents in advance of interacting with them, making those interactions more informed and potentially more enjoyable for the respondents.

Finally, sharing data benefits the broader scholarly community. Sharing data:

- Creates a public good. Sharing data allows them to accumulate, and allows others to analyze them.

- Is economically efficient: doing so helps to avoid costly duplication of data collection, and makes optimal use of the funding that supported the data collection.

- Enhances the instruction of research methods. Students often learn best by “doing,” and what better way to engage them than by using data from real research to teach them (as is already the norm in teaching quantitative methods)? Shared data can also be used to create simple, stylized data sets especially designed for teaching purposes.

- Helps scholars without the resources to themselves collect the data they need for their research to get data they can use to carry out their work.

- Facilitates the formation of research networks and partnerships and the building of broader epistemic communities.

- Allows others to evaluate, validate as trustworthy, and replicate your work, maximizing accountability and knowledge generation.

- May be ethically required: if what you’ve discovered sheds significant light on important dynamics it may be unethical not to share your data.

Reasons Not to Share Data

Given qualitative scholars’ traditional hesitance to share their research data, there must be some very good reasons not to do so. We offer here some reasons why you may not be able to share your data broadly, or share all of your data. Can you think of others?

- First use: given how difficult generating qualitative data can be, you might be concerned about sharing your data before you have had a chance to publish on the basis of them.

- Epistemological concerns: you might see data as a product of the reflexive relationship between you and the people you involved in your study, such that someone who was not privy to the inter-subjective event that produced the data does not have the background knowledge and tacit understandings necessary to interpret them.

- Inappropriate use: you might fear that your data will be used for the wrong purposes.

- Lack of Interest: You might think that your data aren’t of interest to, or couldn’t be useful to, anyone else.

- Language concerns: you might question the value of sharing if you anticipate that the language of your textual or audio data makes it unlikely they will be understood by relevant populations of researchers.

- Resource constraints: you might feel you just don’t have the time or money to invest in preparing your data for sharing.

- Lack of incentives: you may feel that your discipline doesn’t really value the sharing of qualitative research data and that there aren’t any professional rewards for doing so.

- Human participants concerns:

- You may worry that asking respondents for consent to share their data will cause them to decline to participate in your study or will impact what they convey.

- You may have promised your respondents that you would not share the information they provided to you with anyone (and may have even promised to destroy that information at the end of your study).

- You may have collected the data under complete assurances of confidentiality.

- Even if you didn’t promise your respondents anything with regard to data sharing, your data may seem too sensitive for others to see.

- You may doubt that your data can be fully de-identified either due to the form in which you collected them (e.g., video), or because some combination of the collected data (or the collected data and publicly available data) is sure to reveal the identities of human subjects.

- It may seem pointless to share your de-identified data because de-identification caused so much information to be lost, significantly compromising the analytic value of the data.

- You will learn more about sharing human participant data in the next lesson

- Legal constraints and proprietary obligations:

- The archives in which you collected documents may have rules about their dissemination.

- Information may have been provided under a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

- Information may be classified.

- Your data may be under copyright, i.e., the exclusive legal right to use and distribute some works of authorship that is held by their originator, preventing their sharing.

- You may have purchased your data under a licensing agreement that stipulated that they cannot be shared.

These concerns and challenges are important to consider and address. Many of the stickiest challenges relate to human participants and legal constraints, and to copyright in particular. The next two lessons in this module offer guidance to help you to address these very legitimate concerns about, and the very real challenges inherent in, sharing these types of data.

It’s also important to keep in mind that most general guidelines on sharing data, such as those offered by various social science academic associations (e.g., ASA 2018, APSA 2012, APA 2016), take into account that you may not be able to share all of your data; they simply require that you explain why you cannot share the data that you cannot share. Funding organizations and journals in various disciplines have likewise adopted these caveats.

An Ongoing Debate

The discussion about sharing qualitative research data is far from settled. Scholars disagree strongly on what should, can, should not, and cannot be shared. They disagree about when in the research cycle data should be shared, and where. And they disagree about the expected benefits and potential costs of sharing qualitative data.

We have linked in the “further resources” section to parts of the extensive debate about data access and research transparency (DA-RT) in political science. Given its intensity and the variety of perspectives represented, we think it represents an interesting window into these discussions. Similar debates are taking place in disciplines across the social sciences.

We should note that the authors of this course are not neutral parties in this debate. We have published on transparency and data sharing and we are both affiliated with the Qualitative Data Repository, an institution dedicated to enable the sharing of qualitative data. Nevertheless, this module is not intended to advance a particular position. Instead, we want to equip you with the tools to decide, based on the best available information, whether you will share your data, what data you will share, and how.

Exercise

Creating a Data Sharing Policy

- Two of the institutional actors that have been carefully considering all of the questions above are funders and publishers. They need to take on these issues because they must develop policies for applicants and grantees, and authors, to follow. Given the considerations, benefits, and challenges above, how should key institutional actors design policies to encourage responsible data sharing? Pretend you are the editor-in-chief of a journal of your choice. Develop a draft policy that you will translate into author guidelines for providing the qualitative data that underpin articles published in your journal, and accompanying “materials” (e.g., documentation). Your policy should address the following issues:

- Which data should be shared and what in addition to data needs to be shared (“materials”)?

- When in the publication process should data (and materials) be shared?

- Where should data (and materials) be shared?

- What established exceptions should there be?

- Who should judge whether a scholar’s situation fits within those exceptions – or, if it does not, whether an exception should nonetheless be made?

- How will the policy be enforced?

Further Resources

- A 2015 symposium in Qualitative and Multi-Method Research looking at qualitative transparency from a variety of perspectives

- The results of the American Political Science Associations “Qualitative Transparency Deliberations”

- A Zotero library dedicated to sharing qualitative data and transparency in qualitative research created by us.