Sharing Human Participant Data

In this lesson you will learn

- The circumstances under which data garnered through interacting with human participants can be shared

- When you should and should not de-identify data human participants data

- Best practices for de-identifying human participants data

- What to do when you cannot de-identify human participants data

- When and why you might control access to your shared data

- What options for controlling access there are

Initial questions

- What are some of the particular challenges and risks of sharing qualitative data involving human participants?

- Can you envision situations in which a researcher might not need to de-identify data from human participants before sharing them?

- What are some of the implications of placing access controls on data?

Ethics of Sharing Qualitative Data

Qualitative researchers often work closely with human participants, conducting in-depth interviews, focus groups, and oral histories, or engaging in participant observation and ethnography. Most social scientists feel a profound ethical obligation to their participants, and responsibility for ensuring that their research does not negatively impact these individuals. Sharing data generated through human participants research can expose your participants to additional risk. As a result, you need to pay special attention to ethical and legal constraints on sharing such data should you seek to do so.

According to the 1979 Belmont Report, three key principles create the conditions for ethical research:

- Respect – Showing respect for the personal autonomy and agency of your research participants.

- Beneficence – Seeking a balance between minimizing potential risks to individual participants and to society while maximizing benefits to both.

- Justice – Being fair to individual participants, neither exploiting nor ignoring one group to benefit another.

If you are based in the US, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at your home institution is best-placed to help you put those principles into practice – i.e., to collect, use, and share data from human participants in a legal and ethical way. (Most other countries have similar organizations to ensure ethical research practices, though they operate under different, if typically similar, rules). As discussed in Module 1, IRBs are administrative entities established to protect the rights and welfare of individuals who become involved in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which the IRB is associated. If your research will involve human subjects directly or indirectly, as defined in federal regulation, you need to submit an application for review and approval by the IRB at your institution before you advertise the project, or recruit or interact with any human participants.

Concerns with sharing human participants data arise when your research participants would like to remain anonymous (i.e., asked that their identities not be revealed), or requested that the information they conveyed remain confidential. It is unethical not to abide by agreements you made with, and promises you made to, your human participants. Note also that protecting human participants (by keeping their identities or the information they convey confidential) may not be the only kind of protection in which scholars need to engage. For instance, archaeologists and other material culture specialists may need to protect the materials that form part of their research (for example, by concealing the exact location of finds).

Social scientists and information scientists are developing strategies, tools, and technologies to make it easier for you to share the information garnered from your human participants in your research in an ethical way. In Module 1 you learned how to obtain informed consent from your human participants – how to help them to understand how you would like to use the information they provided, how and when and with whom you would like to share that information, to what uses it might be put, and what potential risks and benefits these actions present. Below we discuss two other steps you can take to keep your human participants safe.

De-identifying Data

As part of obtaining informed consent, you may assure interview respondents or focus group participants that you will do your best to prevent their identities from being revealed, and to prevent others from linking them to their answers. In order to keep these promises even when planning to share the data, you can “de-identify” their responses, that is, seek to remove identifying information.

Direct and Indirect Identifiers

- All de-identification begins with removing “direct identifiers” (i.e., pieces of information that are sufficient, on their own, to disclose an identity), such as proper names, addresses, and phone numbers. This is typically straightforward.

- “Indirect identifiers” consist of contextual information that can be used, often combined with other information, to identify a participant. As the amount of information that is available at your fingertips has grown exponentially with the advent and expansion of the internet, our understandings of what type of information might qualify as an “indirect identifier” have also evolved. For example, in a seminal paper, Latanya Sweeney showed that almost 90% of the US population could be identified based on their zip code, date of birth, and gender; even using place (like city or municipality) instead of zip code still allows more than 50% of the population to be uniquely identified. iIndirect identifiers of myriad types are often found throughout the responses and information that human participants convey meaning those data need to be handled with great care.

De-identification Practices

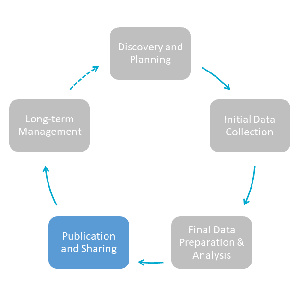

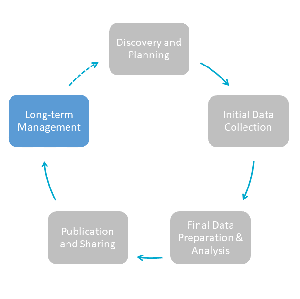

Some good practices will make de-identifying responses from your human participants easier and more reliable. Thinking about and planning for de-identification is an important aspect of data management that you should be considering early on in the planning proccess. Some decisions, such as which data to collect and not-to-collect and what to tell participants about de-identifying data will have significant consequences for how you will use, and if you can share, the data down the line.

- Do not collect identifying information if you do not need it. For instance, you will typically not need full names and contact information for focus group participants. Be mindful, though, that not collecting such information will prevent you from going back to participants with follow-up questions.

- Do plan on engaging in de-identification soon after your interactions with your human participants, marking up elements that require redaction during transcription and/or analysis.

- Do clearly and consistently indicate any changes you make to the original file, e.g., by placing square brackets around passages that have been changed.

- Do not redact xxxxxx or remove […] names and locations. Instead, use pseudonyms,or aggregate nouns (e.g., refer to the state in which an individual lives rather than the town or county) or categories (e.g., “… was born in [1975-1980]” instead of 1977). Do keep linkages in your data intact by applying pseudonyms, aggregate nouns, and categories consistently.

- Do keep a list of de-identification rules, both for yourself, or for your team should you collaborate. This list serves as important documentation when you share your data. See for example the protocol used by Thad Dunning and Edward Camp to de-identify data deposited with the Qualitative Data Repository. This document is separate from the key that links de-identified entries to the actual individuals or entities interviewed, which should not be included when you share your data.

- Do check the document properties of files, which may contain identifiers such as original file names identifying interview respondents.

- Finally, do try to strike a balance between keeping your participants’ information confidential and unnecessarily reducing the analytic value of the data by removing too much information. If you are having difficulties striking that balance, you could ask another subject-matter expert for assistance; some repository personnel or data librarians can also provide abstract rules that you can follow.

When De-identification Is Not Necessary

Not all qualitative data garnered from human participants need to be de-identified.

- When interviews were conducted “on the record,” the resulting notes or transcripts can be shared using the respondent’s name. This may most often be the case for elites who are accustomed to journalistic interviews. Be mindful, however, of local practices: in some countries, it is expected that interviewees will have an opportunity to review the written record of the interaction before it is shared or published.

- Data that are already part of the public record (e.g., public statements by politicians) don’t need to be de-identified.

Limits of De-identification

Complete de-identification of the notes or transcript from an interaction with a human participant (while retaining the analytic utility of the record) is often impossible). To offer an extreme example, if you interview a US Supreme Court justice, no reasonable amount of redaction is going to allow you to keep their identity confidential. Yet even if your respondents are not well-known, you will rarely be able to protect their identities from absolutely everyone. For instance, if you interview people in a small village, you can often mask their identities from other researchers and most everyone else, but their neighbor, knowing that you talked to them, would likely be able to recognize them from shared data. When complete de-identification is impossible, particularly when the data are very sensitive, controlling access to data can be a useful complement to (or replacement for) de-identification.

Exercise

De-identification

- Read the passage in this PDF and then seek to de-identify it as best you can. Your first step should be to create a set of de-identification rules to follow.

Access Controls

As we note above, complete de-identification is often impossible. As such, de-identification, on its own, might be insufficient to protect the identity of human participants. In order to share their contributions to your research project more broadly in an ethical way, additional steps are needed, such as controlling who can access the data, how they can do so, and when. When you store your data in a trusted data repository, you can often request that various types of restrictions be placed on their access. Access controls are sometimes mistakenly viewed negatively as restrictions. In reality, they allow you to share data that would otherwise remain entirely inaccessible. That is, they allow research to be

as open as possible, as closed as necessary

(as the European Union’s Horizon2020 guidelines for research aptly put it).

Types of Access Controls

Access controls can be placed in three broad categories:

Who can access your data? Access to your data might be restricted, e.g., to researchers with a legitimate interest in the data (as proven by a research proposal); alternatively, anyone who wishes to access the data may be required to secure approval from their IRB.

How can others access your data? They may have to use special secure internet connections to download the data and sign agreements about the safe storage and eventual destruction of their copy of the data. In special cases, you may even require that researchers access the data in person at a repository or other location using a computer disconnected from the internet. Some repositories offer hybrid solutions between these two options, such as ICPSR’s “virtual enclave,” which allows remote viewing of data which never leave the server.

When can others access your data? Embargos (i.e., periods when your data are absolutely inaccessible to anyone) can sometimes be used as an additional protection for human participants. Most often, they are relatively short and oriented toward ensuring the ability of the researcher to publish on the data prior to making them accessible to others. In some cases, however, embargos can make valuable data available in the long run by setting a “lifting date” when human participants will be deceased, for instance. Historical archives often have such rules for personal papers.

Using Access Controls

As with engaging in the de-identification of data, using access controls always entails a trade-off: more stringent controls make it less likely the data will be misused but also more difficult for others to access, and thus use and benefit from, the data. While access controls are a powerful, if less-utilized tool for data sharing, they should not be used gratuitously to complicate access to data whose sharing poses no risk.

As the primary steward of your data, it is ultimately up to you whether to place access controls on your data if you share them, and which controls to introduce. However – and while it seems counterintuitive – we generally recommend that you allow repository personnel to offer input, or even guide decisions, on data access and its limitation. Repository personnel will be able to identify potential challenges associated limitations you devise; for instance, if your permission were required for another scholar to access the data, they may become inaccessible if the repository is unable to contact you at some point in the future. Based on your in-depth knowledge of your data and its context and the repository’s understanding of technical options and best practices, you will be able to arrive at a safe – and thus ethical – solution.

Further Resources

- Mosley, Layna. 2013. Interview Research in Political Science. Cornell University Press.

- Further guidance on de-identifying data on QDR.

- Guidance on de-identifying qualitative data by the UK Data Archive.

- ICPSR’s guidance on data sharing. Note in particular the section on data enclaves at the end.