When, How, and Where to Share Data

In this lesson you will learn

- The various places where you can share your research data

- About data repositories and their benefits

- What kinds of data repositories exist

- Some issues to consider when deciding where to share your research data

Initial questions

- If you have already shared some of your research data, where did you do so and what were the main reasons behind your decision about where to share?

- When someone says “data repository,” what sort of image does that conjure up for you?

When to Share Data

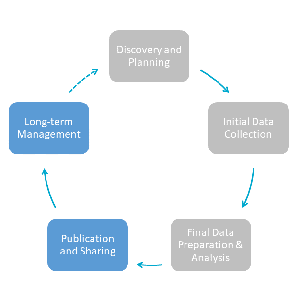

Once you’ve decided which of your research data you will share, and while considering how to address any challenges that sharing your data might pose, another key question to think about is when to share the data you have decided to make accessible. You can do so at any point in the data lifecycle. When you will share what data should typically be captured in your data management plan (DMP). We offer here a (non-exhaustive) list of options for at what point in your research to share data, and some reasons why you might consider each one.

Note that most of these options have as their referent sharing data for the purposes of making a research publication more transparent, rather than for secondary analysis by other scholars or some other use.

- Share data in real-time, as your research progresses. Sharing data as they are collected is rare. Doing so can pose significant logistical challenges and could help other researchers to “scoop” you. The most prominent setting in which real-time data sharing does and should occur is in crises, such as global epidemics. For example, during the Zika virus outbreak, researchers organized global data sharing to quickly address this emergent health crisis. Social science data can be part of such an emergency response, as the importance of anthropological work in combating Ebola demonstrates.

- Share data when you submit the manuscript with which they are associated for review by a journal. Having data available for reviewers allows them to more deeply probe your work and demonstrates the richness of you research. All that said, very few journals in the social sciences require that authors share data during peer review, and consequently doing so is comparatively rare.

- Depending on where you make the data available, you may also solicit, or otherwise receive, feedback from a broader set of peers. E.g., when one of us shared data and code for a paper based on quantitative analysis, together with a preprint version of the paper, we were alerted to issues with the code by an interested reader.

- Share data at the same time that the book or article that they underpin is published. This is likely the most common time to share data. You may do so because it is a requirement of the journal in which you publish: where journals require data sharing, they typically require it as a condition of publication. Alternatively, you may simply want to provide readers with background materials for you work.

- Share data after an embargo period. Embargos can have different functions. You may write an embargo into your grant’s DMP (“data will be published 3 years after completion of the grant”) to allow you first use of your data while assuring your grantor that the data will eventually be made accessible. You may also impose much longer embargos (e.g., 50 or 100 years) to protect human participants. Such embargos are common in historical archives but can also be applied by data repositories.

How to Share Data

Another key question to ask yourself is how and where you will share your data. There are lots of options – we begin by offering a (problematic) subset:

- You could share your data on an ad hoc basis by emailing them to twhomever requests them, or sharing them via a Dropbox or Box.com folder.

- You could post your data on your own website.

- If the data emanated from a broader research project, you could post them on that research project’s website.

- If the data are associated with a research article, you could include the data as supplementary material for the journal’s publisher to store.

These solutions, however, pose various types of problems.

- Sharing your data on an ad hoc basis with people who request them means your data aren’t really accessible. Don’t you want as many people as possible (within ethical and legal constraints) to be able to learn from and reuse your data?

- In the first three scenarios above, you remain the steward of the data: do you have the technical knowledge and resources to guarantee the accessibility and long-term preservation of your data when, for instance, your institution changes technologies or you change institutions?

- Then there’s the issue of link rot (i.e., hyperlinks pointing to web resources that have become unavailable). To give an example of the prevalence of this problem, more than half of the reproducibility links in articles from the American Political Science Review between 2000 and 2013 couldn’t be accessed in 2016 (Gertler and Bullock 2017, 167) [ungated copy]. If you rely on personal or even institutional websites for data sharing, you put your data at risk of link rot.

- Finally, while publishers have significant experience in preserving digital publications, they rarely extend their preservation promises and practices to supplementary material and may not prioritize making such materials accessible to the broader research community.

The bottom line is, you’re a scholar! You’re equipped to generate and analyze data. You don’t have, and shouldn’t need to have, the skills necessary to properly care for and preserve research data for the long term.

Don’t let this be your research data!

The same goes for journals, whose core mandate is to publish articles, not preserve data. Instead of exercising the options above, we encourage you to store your data in an institution specifically created for this purpose, i.e., in a data repository. As you’ll learn more about below, a repository is “a final destination” for data that allows for their long-term publishing and preservation. There are a few kinds to choose from, and lots of things to consider when you’re making your choice.

Exercise

Link Rot

- The list of broken links that Gertler and Bullock note (in their 2017 article in PS) that they found in the American Political Science Review (see above-cited article) is part of the data accompanying their PS article; they shared the data through Harvard Dataverse here in the file “brokenReproducibilityURLs.tab”. Download the file, open it in Excel, and find the first five links marked as “Did not find resource”. What sorts of websites are these? Can you still find the linked content using the Internet Archive’s Way Back Machine?

Where to Share Data: What Data Repositories Do

Most data repositories curate research data and preserve them for the long term. Curation is an umbrella term that describes a set of activities: managing, maintaining, validating, and adding value to research data. Curation increases the value and quality of data as a research product, augmenting their understandability and usability by the scientific community. Preservation refers to protecting and prolonging the integrity of research data and their associated metadata for the long term. Data repositories are generally stable over time, helping to ensure the long-term preservation and security of your data.

Given the characteristics of qualitative research data, and the practical, ethical, and legal challenges that sharing such data sometimes poses, even if you carefully manage your data, they often need to be curated by experts in order to be findable by and accessible to other scholars. The staff of repositories that often work with qualitative data are familiar with and alert to the special challenges posed by sensitive data, and help depositors to make decisions on how to share their data ethically and legally. In the next section we discuss types of data repositories.

Most full-service repositories offer the following services:

- Make your data easier for other scholars to discover and access

- Repositories are fully searchable and often indexed broadly.

- Repositories assign digital object identifiers (DOIs) to data.

- A DOI is a unique, persistent character string that can be assigned to any digital object (e.g., a dataset, a 15-second interview, or a piece of documentation). It’s basically a tag that remains fixed over the lifetime of the digital object. Referring to an online document by its DOI provides more stable linking than simply referring to it by its URL.

- Make your data easier for other scholars to use and cite

- Repositories publish documentation and other materials that facilitate the interpretation and re-use of data.

- Repositories develop and standardize metadata, and associate relevant and important metadata with your shared data.

- As we began to explain in Module 2, metadata are structured information describing multiple characteristics of your data. Some examples of metadata that might be associated with the data you deposit in a repository are your name, the dates during which the data were collected, and the area of the world to which the data pertain.

- Separate data files may also have additional item-level metadata associated with them.

- Provide tools that allow you some control over who accesses, downloads, and uses your data, and how they do so

- Repositories offer authenticated online access to data.

- Repositories allow you to establish user-access controls for your data when these are necessary to protect confidentiality and personal privacy as required by law and the ethical standards of your research community.

- Collaborate across disciplines to achieve interoperability among scientific communities

- Repositories often allow the “harvesting” of their metadata through a dedicated protocol, facilitating the development of search interfaces covering many data repositories.

Exercise

Data Sharing SNAFU

- Watch the short video above and write down the various types of problems created by the ad hoc sharing arrangement for which the bear on the left opted. How would these problems have been mitigated if the bear had deposited his data in a data repository? While the bears are discussing quantitative data, would the challenges be the same for qualitative data?

Types of Data Repositories

There are several different kinds of data repositories.

Self-service repositories are the newest type. Most were founded after 2000. They are typically open to all research data (and in some cases other materials). Such venues probably hold the largest number of individual datasets worldwide.

- Advantages

- Convenience: they allow easy upload of data of any kind for all researchers.

- Cost: both deposit and download are free of charge.

- Disadvantages

- Heavy reliance on the expertise and efforts of depositors.

- Typically, deposits are either not reviewed/curated or are only minimally reviewed/curated by staff; for instance, often the repository does not check that deposited files are valid (i.e., open correctly in the specified software)

- Depositors are responsible for supplying cataloging information.

- The repository’s preservation practices do not guarantee accessibility over time; for instance, most self-service repositories do not protect against file-format obsolescence (the inability to open old files with currently available software).

- Examples:

- Figshare (a for-profit company)

- Zenodo (run by CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research)

- Harvard Dataverse (run by the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University)

Institutional repositories are generally operated by college and university libraries, or by other research institutions. They accept pre-prints, working papers, and, increasingly, research data generated by affiliates of the institution with which they are associated.

- Advantages

- The proximity of your institutional repository makes it easy for you to contact it with questions across the data lifecycle.

- You may have a great deal of trust in this repository right at your home institution.

- Libraries have a lot of expertise in the preservation of digital formats.

- Disadvantages

- Such repositories have traditionally been more concerned with holding and making available researchers’ publications than with facilitating access to the data underlying their research, and thus their personnell’s skills with regard to the latter are under development.

- Libraries (and thus institutional repositories) may lack sufficient information technology and subject-specific capabilities to provide specific curation, preservation, and dissemination guidance and services (Johnston et al. 2017).

- Examples

- Many research institutions worldwide have institutional repositories. These examples are not representative. All are US-based institutional repositories at institutions that have made significant investments in creating local data services.

- Duke Digital Repository

- Deep Blue Data at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- Johns Hopkins University Data Archive

- Data Repository at the University of Minnesota (DRUM)

Domain repositories focus on a specific discipline or group of disciplines (e.g., “social science” or “earth science”) and provide specialized services for data commonly used in those disciplines. Domain repositories have the longest history of the types considered here.

- Advantages

- Domain repositories help you deposit your data, and they then curate and preserve the data.

- Domain repositories are commonly best-equipped to store, preserve, and provide access to sensitive data.

- Domain repositories link data to publications in which they are used and/or cited and showcase data holdings via blogposts, press releases, or infographics.

- Domain repositories often monitor how the data they store are used; this makes it easier for you to get credit when the data you generated are used by others.

- Disadvantages

- Sometimes domain repositories put data behind a paywall that may limit the number of people in the U.S. and around the world who have access to your data.

- Sometimes domain repositories charge for depositing data. The relevant costs may be born by institutions, but sometimes you might have to pay them.

- Examples

- The Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) (University of Michigan)

- The Roper Center’s public opinion archive (Cornell University)

- The Odum Institute’s Data Archive (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

- The Qualitative Data Repository (QDR) (Syracuse University)

- Open Context, dedicated to archaeological and related data

Other repositories are “hybrids” – some combination of the types just mentioned.

- Dryad – began as a domain repository for bio-medical data, but now accepts data from many disciplines, and performs curation services.

- Re-Share (UK Data Service) – a social science self-publishing repository run by and alongside a fully curated domain repository; this venue offers reduced but still significant curation work.

- Open ICPSR (ICPSR) – a social science self-publishing repository run by and alongside a fully curated domain repository. Data published on Open ICPSR are minimally curated; a metadata review is performed after publication

Exercise

Getting to Know Your Repository

- Find the web site of the repository at your institution and poke around a bit. (If your institution doesn’t seem to have an institutional repository, try to find the institutional repository at another institution that is similar to yours or with which you’re familiar.) Then find the web site of another kind of repository (choosing from one of the categories above) and poke around a bit. What similarities and differences do you notice? You might think about these first with regard to the content of the venue, then from the perspective of someone who might wish to deposit data in the venue, then from the perspective of someone who might with to access data from the venue.

Evaluating Options and Choosing a Sharing Venue

Now that you know a bit more about some of the venues in which you can share your research data, how will you decide among them? There are lots of issues to consider when making your choice. You might think about:

- How much does it cost to deposit your data in the different venue choices?

- Are you going to want direction and assistance with depositing data – is it important to you to be able to interact face-to-face with the people who are handling your data? Or would you rather be able to post your data quickly and efficiently without interacting much with repository personnel, answering questions about curation, etc.?

- How findable and accessible do you want your data to be for other scholars?

- How much do you want and need your data to be carefully curated?

- How sensitive are your data?

- Will you need to place some kinds of access controls on your data?

- How well-described and automated do you want the methods for accessing your data to be?

- To what types of scholars do the different venue choices seem to cater, and does that match the audience with whom you would like to share your data?

- Will other scholars who wish to access your data be charged?

- How easily and effectively do you want other scholars to be able to reuse your data?

- What kinds of reputations do the different venue choices have?

- How much do you trust the different venue choices to keep your data safe?

- Does the venue have Core Trust Seal certification?

- Can the venue issue DOIs?

It could be helpful to actually write out the answers to these questions, ideally as part of working on your DMP, and then compare what seems to be important to you with the advantages/disadvantages of the various types of venues listed above. Do your answers seem to point you towards one type of venue or another?

Further Resources

- Some examples of shared qualitative data:

- Data by political scientists Alisha Holland (Data for: Forbearance as redistribution) and Matthew Hitt (Replication Data for: Inconsistency and Indecision in the United States Supreme Court), both supplementing monographs, show complex, multi-method projects containing different types of quantitative and qualitative materials. (Qualitative Data Repository)

- Data by health researcher Adanna Chukwuma contain well-documented, de-identified focus group discussions. (Qualitative Data Repository)

- The “School Leavers Study” by Ray Pahl contains hundreds of essays by students on a British isle, imagining the life ahead of them. (UK Data Services)

- The data journal Nature Scientific Data maintains a list of recommended (mostly domain) repositories across disciplines.