Finding and Citing Data

In this lesson you will learn

- How to find research data that are suitable for re-use

- Why citing data is important in scientific writing

- The main components of a data citation

Initial questions

- How do you go about finding research data on a given topic?

- Have you ever cited data – yours or someone else’s?

- Have you ever wondered why researchers cite papers and books, but rarely software or data, even though the latter play a crucial role in enabling research?

- If you have seen data cited, what form did those citations take?

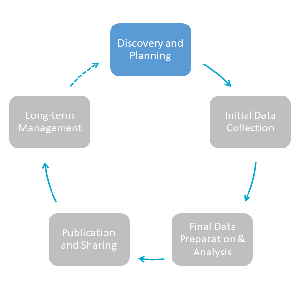

Finding Data

Finding scholarly articles has become much simpler thanks to powerful search engines like Google Scholar, Web of Science, dimensions.ai, etc. Research data, as you have likely experienced yourself, are much harder to find. There is currently no search engine or catalog for research data that is remotely comparable to the power and coverage of those for articles. Your best bet for finding data is, therefore, a multi-faceted strategy. Here are some things you can try:

- Use search engines.

- DataCite, the DOI provider for most data repositories, offers a search engine. The search covers about 6.5 million entries, but does have a fair number of duplicates and includes individual data files.

- Google offers a new dataset search. The number of datasets that are searched is unknown, but much of the DataCite catalog is included.

- Start with a literature search. You’re likely using some version of this strategy already, but it may be helpful to expand how you think about the goals of your literature search to include a systematic “data search”. Empirical social scientists are increasingly citing, or at least linking to, data they use. Take advantage of this and find what data are being used in papers related to your work.

- Ask your librarian. Most research universities have dedicated librarians for research data – in some libraries there are entire working groups. One of the core qualifications of data librarians is the ability to find relevant data.

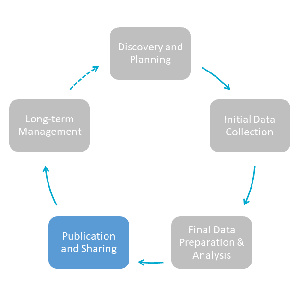

Citing Data

As you deploy data – including your own data! – as evidence in your research products, you should cite them as you would cite any other resources to which you refer. By using formal citations (as opposed to just linking to or mentioning the data you use), you make sure that readers can find the data you reference. Correct and complete citation, then, is a key aspect of research transparency. In addition, proper data citation allows the scholar who collected or generated the data to get appropriate credit. Citing research data also serves as an acknowledgment that data are a product of value themselves, distinct from publications that draw on them.

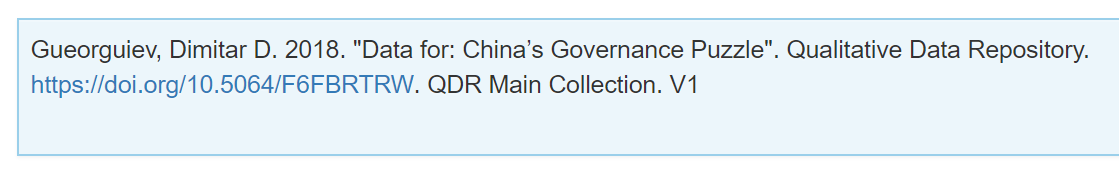

Components of a Data Citation

Like any other citation, data citations contain author(s), a year of publication, a title, a publisher (the repository in which the data reside, for instance), and possibly a version number. Most data repositories will also assign a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) to data, which always begins with 10. Preceded by “https://doi.org/” the DOI provides a permanent link to the data.

Where it exists, the DOI should always be part of the citation. DOIs are part of a broader system that provides metasearch functionality for repositories that issue DOIs. For instance, you can search across all datasets that have a DOI on search.datacite.org. The DOI system makes it a lot easier for scholars who generate data to get credit when others cite and reuse their data, and a lot easier for scholars to find data relevant to their work.

For instance, each time a dataset with a DOI is cited in a journal article (which also has a DOI), the organization registering the journal article DOI (Crossref) catalogs the event, establishing an automated citation count.

Many data repositories include recommended citations for data:

You can use that citation or adapt it to your citation style of choice. Increasingly, reference managers such as Zotero and Endnote will let you import citation data from data repositories and produce correctly formatted citations.

Citing Your Own Data

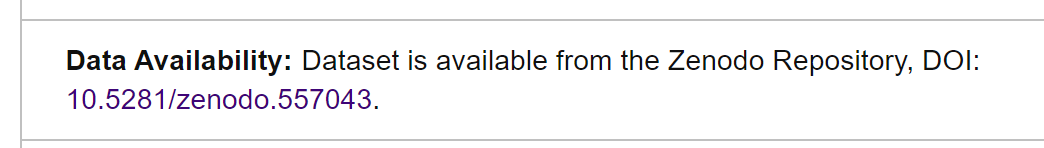

When citing your own data in an article, you will typically include references in two locations. First, the citation will appear in a “data availability statement,” which is placed on the article’s abstract page on the journal web site or in the first footnote.

Second, the data should also be cited formally in the bibliography of the article. While data availability statements are fairly standard in published articles, including the data in the bibliography is not. Doing so is important, however, as it helps your article and data to stay linked together and lends more visibility to the data. We strongly encourage this practice.

In both cases, remember to include the DOI.

Citing Other Researchers’ Data

When you use other researchers’ data in your written work, cite them as you would any other scholarly contribution on which you draw. If the data are available from a data repository, always refer to the repository copy in your citation: repositories are set up to ensure that the data will still be available, and findable using the citation information they provide, many years ahead.

Some large data projects, such as the World Value Survey, self-archive, meaning the project holds and disseminates the data rather than publishing them through a data repository. In almost all cases, they will recommend a citation format, which you should follow, taking particular care to cite the exact version of the data you have used in your work.

Beyond Citation

In some instances, additional steps beyond citing data may be warranted. For instance, if your work draws on (and cites) a large-scale data project and you only use a subset of the data produced by the project, you should describe how and why you extracted the particular subsets of the data that you used in your study.

Depending upon how central to a particular publication the data you re-used were, you might even consider offering the scholar who generated those data co-authorship on your publication. This practice is currently more prevalent in the natural sciences, but may be worth considering in the social sciences as disciplines begin to place greater value on data generation. An interesting alternative that has appeared in the medical field is to list “data authors” (Bierer, Crosas, and Pierce 2017) on publications – signaling that those scholars contributed to data generation but did not collaborate on the actual writing of the publication (and don’t necessarily concur with its conclusions).

Either of these alternatives raises the profile of data and those who create them, emphasizing the contributions they make to knowledge generation.

Exercise

Data Citations

- Find two recent research articles in your field that rely on publicly available data (either shared by the authors themselves or by others). Do they include data availability statements? Are the data cited in the bibliography? If the answer to either of the questions is no, how would a data availability statement/bibliography entry have looked?

Further Resources

- Michigan State University provides an excellent guide to finding data and statistics

- You can learn more about DOIs, why they are useful, and how they work is in this article by Sebastian Karcher.