Creating a Data Management Plan (DMP)

In this lesson you will learn

- How to create a data management plan (DMP)

- How to use tools like the DMP Tool to create a DMP

- How to assess a DMP

- How to treat your DMP as a living document

Initial questions

- Have you had to write a DMP for a grant application or some other purpose?

- Have you used any tools to help you to write a DMP?

- Have you wondered how your DMP would be judged?

What Is a Data Management Plan (DMP)?

So far we have talked about data management and the importance of planning. A Data Management Plan (DMP) is a document that specifies your plans for data management for the whole duration of the project. The plan summarizes the various decisions you took while planning your data management. Broadly, the plan should cover the following topics:

- The types of data you expect to collect,

- How those data will be documented and organized,

- How the data will be stored and kept secure, and

- How the data will be shared (or why not) and stored for the long term.

We provide more detailed instructions below.

Why Write a DMP?

In many cases you will write your data management plan because a funding agency requires it – in the US, for example, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has required data management plans since 2011. Different funders have slightly different requirements for DMPs, but the NSF’s requirement of a 2-page document is fairly typical. An important goal of your data management plan, then, is to convey to the funder that you have thought carefully about data management.

We would encourage you, though, to compose a data management plan even if you are not required to do so by a funder. Having your plans for your data written out helps keep you organized and on track as you conduct your research project. Having written plans can be especially useful if you need to coordinate the activities of a research team – including just a couple of RAs. Having your data management plans written out also allows you to communicate those plans to others. At QDR, for example, looking at researchers’ DMPs allows us to quickly understand their goals and needs, helping us to offer them the support they need.

From the field

The NSF and other agencies are starting to look at data management plans more and more closely. In 2012, barely adequate DMPs were routinely accepted. That is no longer the case. Take the DMP portion of your grant seriously.

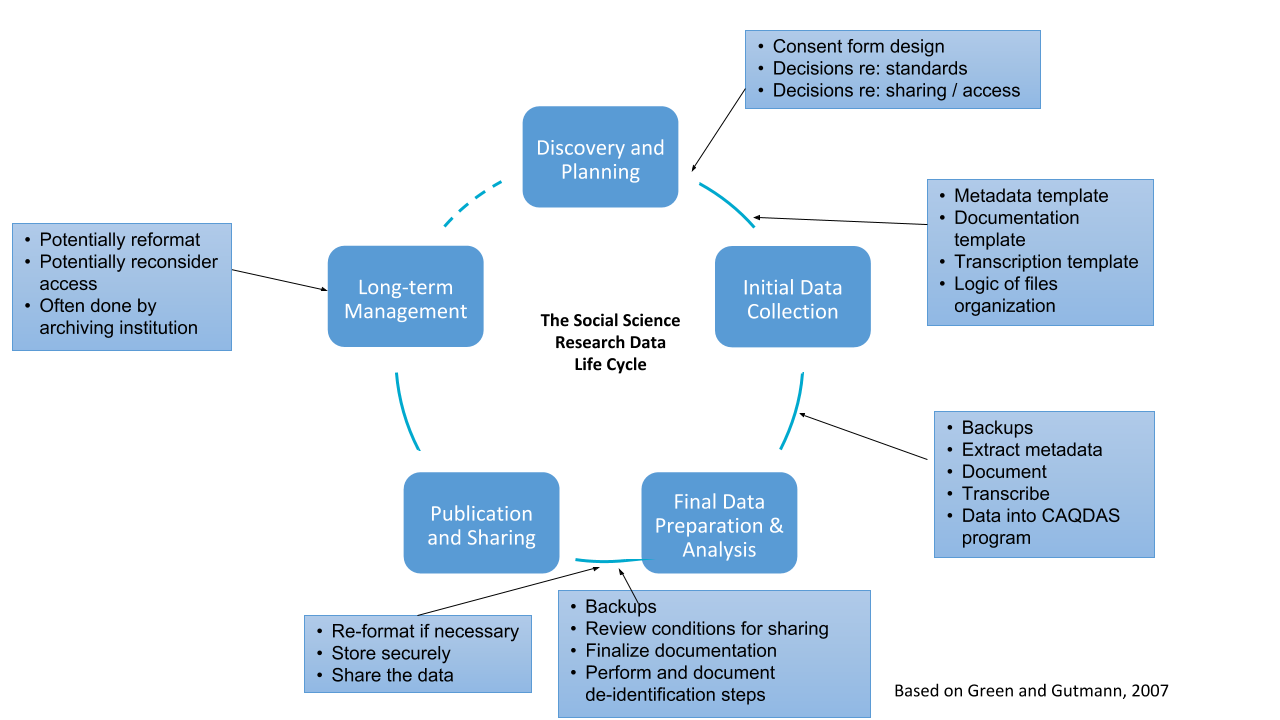

A good way to think about writing a DMP is ask yourself the following question: “How can I demonstrate that I have carefully thought about what my data needs will be at each stage of my research and data lifecycles and that I have identified specific and well justified procedures to meet those needs?” How do you start thinking about this conceptually? The data lifecycle we introduced in the previous lesson provides you with a helpful heuristic.

Exercise

Using the Data Lifecycle for Planning

- Using a depiction of the data lifecycle (you can draw one by hand or download and print a PDF version from here), write out which data management planning and/or data management steps you should take at every point in the lifecycle.

Tools for Writing a DMP

There are a lot of resources for writing DMPs. We have listed some at the end of this lesson. We would like to particularly highlight two resources.

QDR has designed a data management checklist specifically for qualitative researchers to make sure their DMPs cover all of the most important topics. For every topic we provide examples, where possible from qualitative research. We also include tips based on our work advising researchers on their DMPs. You can use the checklist both proactively as a guide to writing your DMP, or to check that an existing DMP covers everything it should.

Still, you may find it difficult to start writing such a plan. You may find the DMP Tool, produced by the California Digital Library, helpful. The DMP Tool provides a large number of templates, based on funder requirements, and helps you to structure your DMP according to those templates, guiding you through the process with questions. When you are done, it provides you with a neatly formatted DMP. The language of the DMP Tool can be a bit abstract; using the tool and QDR’s checklist in tandem can help you navigate the various topics.

Exercise

Using the DMP Tool

- Create an account for the DMP Tool (if possible through your university) and write a very brief DMP. Your plan does not need to be very detailed (for now) – the goal is to get a sense of the tool.

Some Key Elements of a DMP

Tools such as our checklist or the DMP Tool offer a comprehensive overview of the contents of a DMP. Here we simply highlight some particularly important or frequently misunderstood issues.

Personnel: As a young researcher, you may not think of yourself as leading a “team,” but chances are you will be using research assistants, or potentially contractors like transcribers, translators, or even stringers before you publish your research. You should consider what parts of your data particular team members can access, how you provide (and restrict) access for them, and how you will train them to manage your data responsibly.

Data types: Generally, storing your data in standard file formats is ideal. Where you rely on proprietary, specialized formats, you are at the mercy of the company supporting these formats. Using proprietary formats is not always avoidable (e.g., most qualitative data analysis software like NVivo or atlas.ti stores data in a proprietary format), but do not rely on them if you don’t need to do so. Moreover, consider including in your DMP alternative storage and dissemination formats for such data.

Data volume: DMP guidelines often ask you to specify the volume of data. Do not feel like you need to be overly precise here. The purpose of this is for you to think of adequate storage facilities, so the important thing is to be in the right ballpark: you want to know if you need to store 1GB or 1TB of data. It doesn’t matter whether it’s 1GB or 2GB.

Metadata: We will talk more about metadata in Module 2, but a useful way to address questions about metadata is to talk to the repository you want to use to share your data. Repositories commonly follow metadata standards and can tell you what those are.

Data sharing: If you cannot share some of your data – or cannot share any of them (e.g., because you interviewed people who would be put at acute risk should the interviews become public) – you should specify the rationale clearly and specifically in your DMP. Funders want to understand the details of what will prevent sharing.

Assessing DMPs

How do you know that your DMP is good enough? When working with researchers, we have often found that assessing other researchers’ DMPs is a good way to think about this. We use a rubric developed by a group of US librarians to assess DMPs submitted to NSF for their compliance with NSF criteria for such plans (Whitmire et al., 2015).

Exercise

Assessing DMPs

- Find the rubric by Whitmire et al. here and a scoresheet for the rubric here. Use this rubric to evaluate the data management plan by Fisher and Nading (2016) here. (Alternatively, when working in a group or with a partner, you can exchange DMPs and assess each other’s). For now, use the example language in the rubric to score the DMP.

- As you work through the rubric, try to not just think about what you would improve about the DMP, but also where the rubric itself might fall short.

DMPs as Living Documents

Writing a DMP entails thinking ahead to situations and circumstances that may arise as you conduct your research, and planning for them. Of course, none of us can predict all the eventualities of a multi-year research project. This is why there is a movement to treat DMPs as “living documents” – plans that grow and evolve together with your project. For example, adding team members or collecting data you didn’t originally plan to collect will lead to amendments in your DMP to reflect and accommodate these changes. You should either save a new, date-stamped copy of your DMP every time you amend it or use a version control system such as git. Used this way, your DMP become a valuable piece of documentation for your project and also a crucial point of reference for you. We strongly recommend you to consider this approach especially for complex research projects.

Looking ahead, information specialists are also working on making DMPs active. With active DMPs, if you mentioned a data repository as part of your planning, the repository would automatically be notified of this. The DMP would also send you automated reminders on key dates specified in the plan. Active DMPs would also let funders check easily that you have complied with the promises made in your DMP (and thus your grant application). You can read more about this vision in a recent paper by Simms and Jones (2017).

Further Resources

California Digital Library. 2017. DMP Tool. https://dmptool.org/

Fisher, Josh, and Alex Nading. 2016. “A Political Ecology of Value: A Cohort-Based Ethnography of the Environmental Turn in Nicaraguan Urban Social Policy.” Research Ideas and Outcomes 2 (May):e8720. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.2.e8720.

Qualitative Data Repository. 2017. Data Management Checklist. https://qdr.syr.edu/drupal_data/public/QDR%20-%20Data%20Management%20Checklist.pdf

Simms, Stephanie Renee, and Sarah Jones. 2017. “Next-Generation Data Management Plans: Global, Machine-Actionable, FAIR.” International Journal of Digital Curation 12 (1):36–45. https://doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v12i1.513.

Whitmire, Amanda, Jake Carlson, Brian Westra, Patricia Hswe, and Susan Parham. 2015. “The DART Project: Using Data Management Plans as a Research Tool.” Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/kh2y6.