Principles of Documenting Data

In this lesson you will learn

- What “data documentation” is and what good documentation includes

- At what point in your research you should document your data

- What different types (or “levels”) of documentation exist

Initial questions

- You have probably already documented some of your data – can you think of some ways you did so? Were you thinking of those tasks as “documenting” your data?

- Why is it important to document your data?

- Are there “right” and “wrong” ways to document data?

Documentation Overview

At the core of good data management is documentation. Documentation introduces your data, provides a detailed description of their key attributes, and contextualizes them Your documentation should describe what you did and why you made the choices you made.

Documentation can be written at many “levels” and comes in many forms (as described below). Together, all of the documentation associated with a research project should answer a series of important questions (although any particular piece of documentation may only answer a subset of those questions).

- What was / is the context of data collection (empirical, theoretical, and/or normative)?

- How did you generate / collect the data?

- In what form are the data (e.g., “interview transcript”)?

- What are the data about (i.e., what is your research about)?

- How are the data formatted, structured, and organized?

- How did you transform or manipulate the data (e.g., modify format)?

- How did you validate / assure the quality of the data?

- What ethical or legal limits (e.g., confidentiality, copyright) are there on access to / use / re-use of the data?

- (Perhaps) How did you analyze the data?

Clear, thorough documentation is helpful to you (and the “future you”), to other members of your research team (if you have research assistants or are otherwise working collaboratively), and to scholars who may re-use your data later in time. Good documentation helps you and others to get clarity on and remember details about your data and its provenance, to assess the quality and evidentiary value of the data, and to avoid misinterpreting or incorrectly using the data. If you share some or all of your data (as discussed in the next module), good documentation improves the processing and archiving of your data, and facilitates the creation of good metadata and an accurate catalog record for a published data collection.

The specific types of documentation that might best introduce, describe, and contextualize data differ from research project to research project. Below we offer some examples of types of data documentation that you might produce as you carry out a research project:

- Questionnaires used for surveys or semi-structured interviews

- Guidance materials used for team-based fieldwork

- Instructions for focus group facilitation

- Consent forms and information sheets

- Approved IRB application

- Permissions or licenses from copyright holders

- Description of methods used to analyze the data

- Description of fieldwork and project context

- Description of how derived materials (individual files or variables) were created

- Coding schemas

This famous quote, originally referring to computer code, applies just as much to your data. Be kind to your future self.

When to Document Data

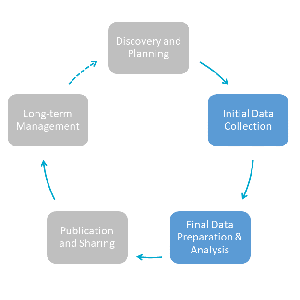

Documentation – and creating it – play important roles throughout the lifecycle of your research project and the lifecycle of your data. You engage in different documentation tasks at each stage of the research and lifecycles.

- When you are beginning to plan your research think of the different types of documentation you will need and create a template for each type. For instance:

- Generate a template for your archive log.

- Create a template for “informal metadata” from interactive data collection (the next lesson talks more about metadata).

- Create a field observations template (see the next lesson for more on this type of template).

You create the bulk of the documentation for a particular project as you are collecting / generating data, using the templates you created.

- As you analyze your data and write you pull together, organize, and finalize your documentation.

In particular when you are deep in the trenches generating data, you may feel that working on documentation is not the best use of your time. To the contrary, while you’re collecting / generating data is the best moment to document them. Systematically capturing all relevant information about your data as you gather / create them – i.e., when that information is most available and clear to you – will allow you and others to make the best use of your data.

Levels of Documentation

It is helpful to think of documentation by the unit it documents. Some information refers to the whole project, while other information refers to an individual file. No matter at what level you are documenting data, documentation files should be clearly labeled using a consistent labeling schema.

Project Level Documentation

Project level documentation describes the general parameters of your research project. This type of documentation typically begins with a high level overview of your project and its focus. Thereafter, you describe the “what,” “who,” “when,” “where” and “how” of data collection / generation.

- Describe the what of your data

- What types of data are you collecting?

- In what form are they (i.e., focus group transcript)?

- What is the substantive content of the data – what are they about?

- Document anyone who has or will contribute to a project – research assistants, translators, transcribers, interviewers, coders, etc. – and what role they played.

- Document when any important project-related events occur.

- Describe the “where” of your data collection – contextualize the collection process(es) in space and time.

- Describe how you / your team collected / generated the data, detailing and justifying important methodological choices, for example:

- How did you pick interview respondents (and why did you do so as you did)?

- How did you recruit focus group participants (and why did you do so as you did)?

- How did you pick research sites (and why did you do so as you did)?

- How did you select archives and archival documents (and why did you do so as you did)?

- If you deviated from your original data collection plans, in what ways and why?

As you generate data you should keep informal but complete and accurate lists to document these activities. Spreadsheets are a great way to keep track of, for example, which websites you consult, whom you interview, or what documents you review. Later, you can formalize these lists into clear documentation.

File Level Documentation

File-level documentation reflects the contents of an individual data file. Often, you keep track of this information in the header of a file/document. Alternatively, you can record information using the file “properties”, which makes descriptions of a file and its content visible to your computer’s operating system. You can construct templates for either type of documentation, and different types of data files, before you start your research so the information is structured similarly across different files of the same type.

Software tools can help you create file-level metadata. You may already use a reference manager like Zotero, Mendeley, or Endnote to store academic work (e.g., scholarly articles) and metadata about it. You can also use these tools to store newspaper articles, archival documents, or even interview transcripts, and descriptive information for each document. Such file-level metadata. might include, for instance, date collected, location collected, people involved, main topics, etc.

There are also other tools that can help you to keep track of documents. For example, the Tropy software was developed by historians to facilitate keeping track of and organizing large numbers of pictures taken in archives.

Exercise

Documenting Your Data

- Make a list of three types of documentation at the project or file level that you will need to create for a research project you are carrying out. For each item, indicate in what form you’ll create the documentation (i.e., as a Word doc, Excel spreadsheet?) and offer a short description of the types of information you’ll include in that documentation.

- Think through three ways in which creating and having this documentation will help you.